Ready to Order

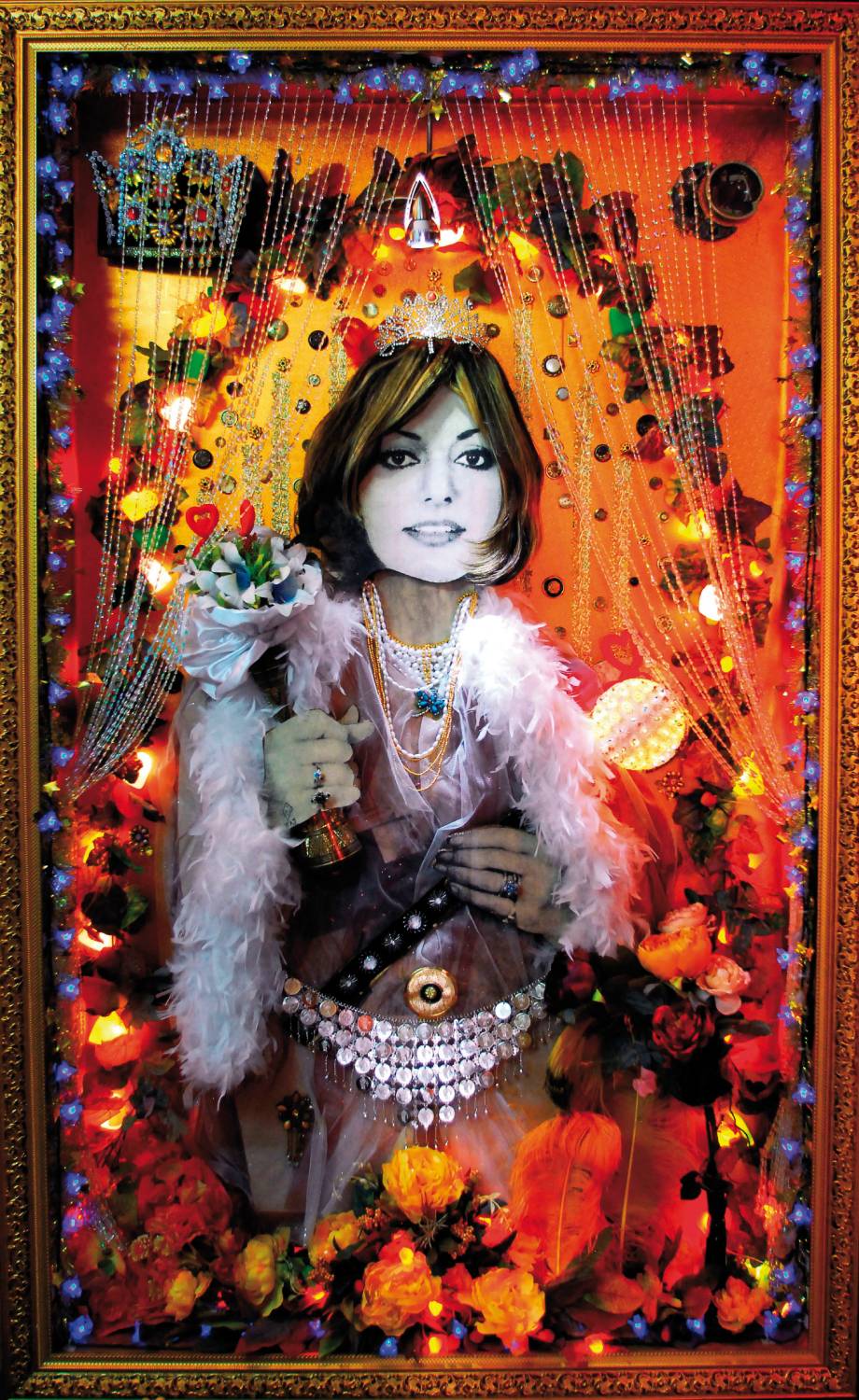

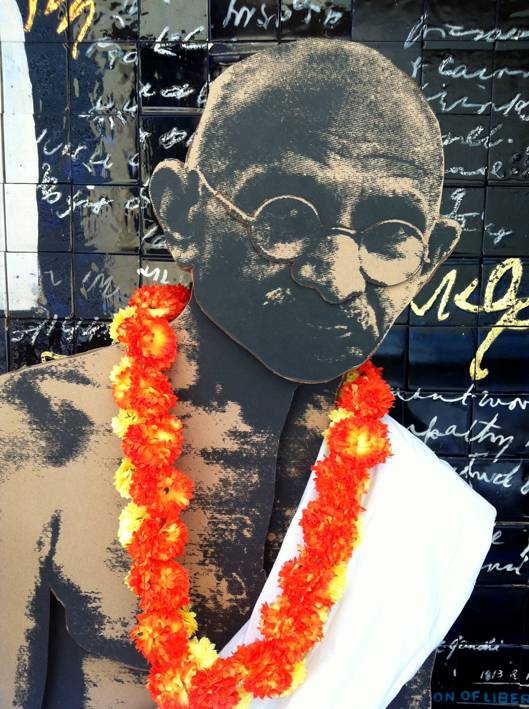

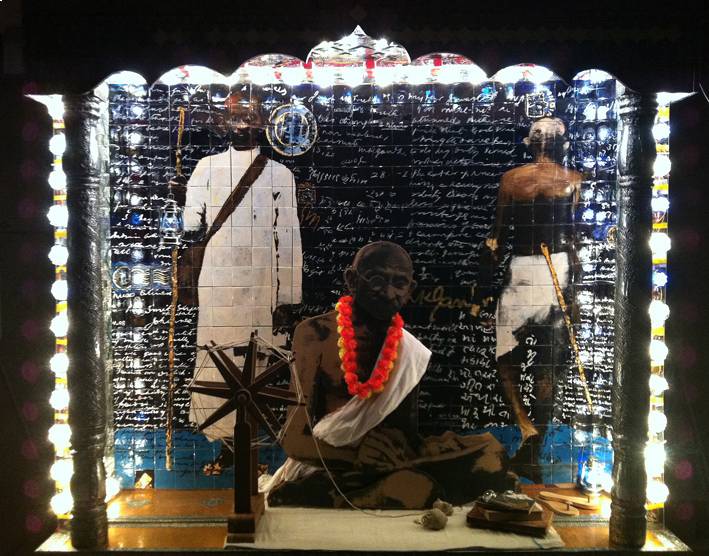

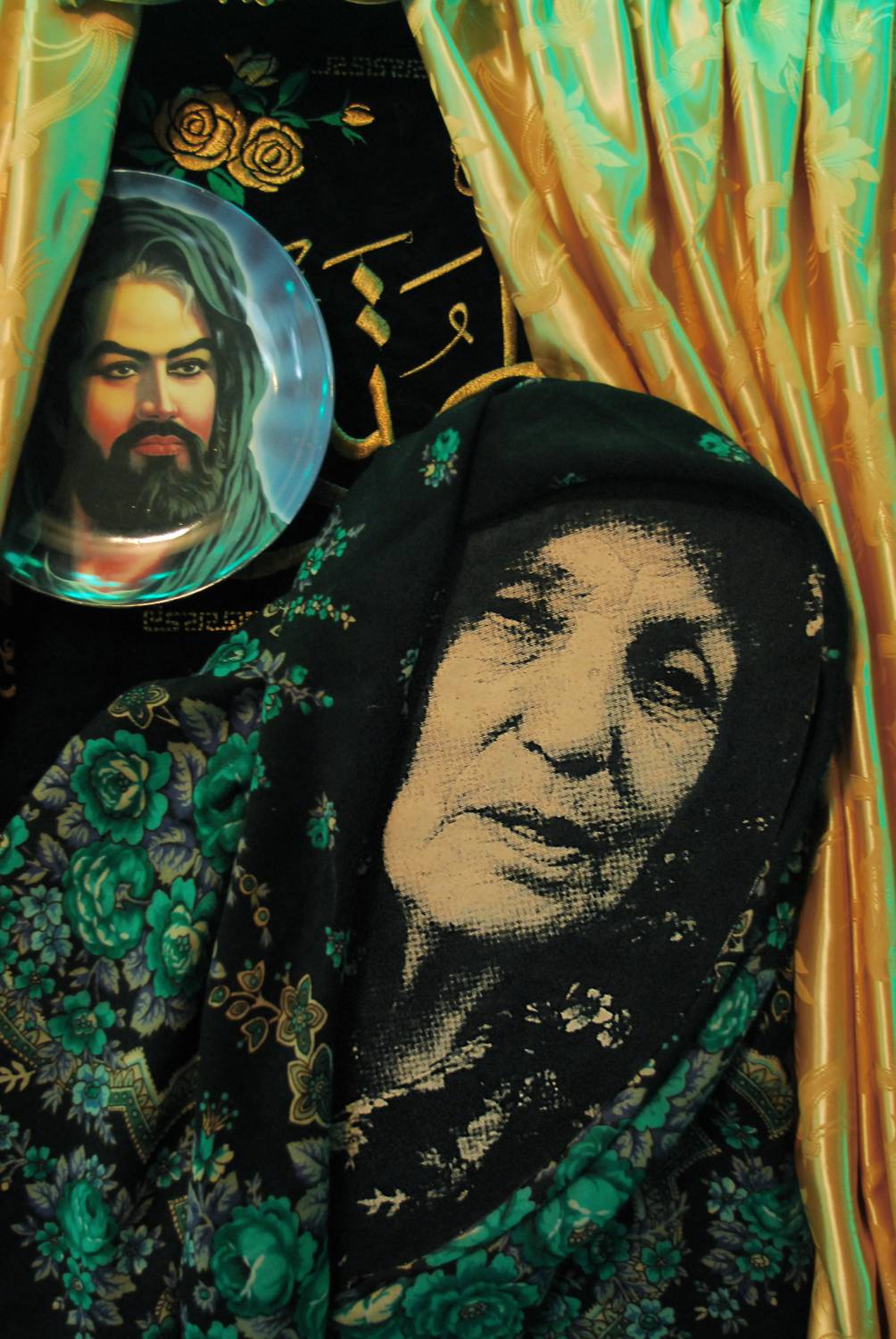

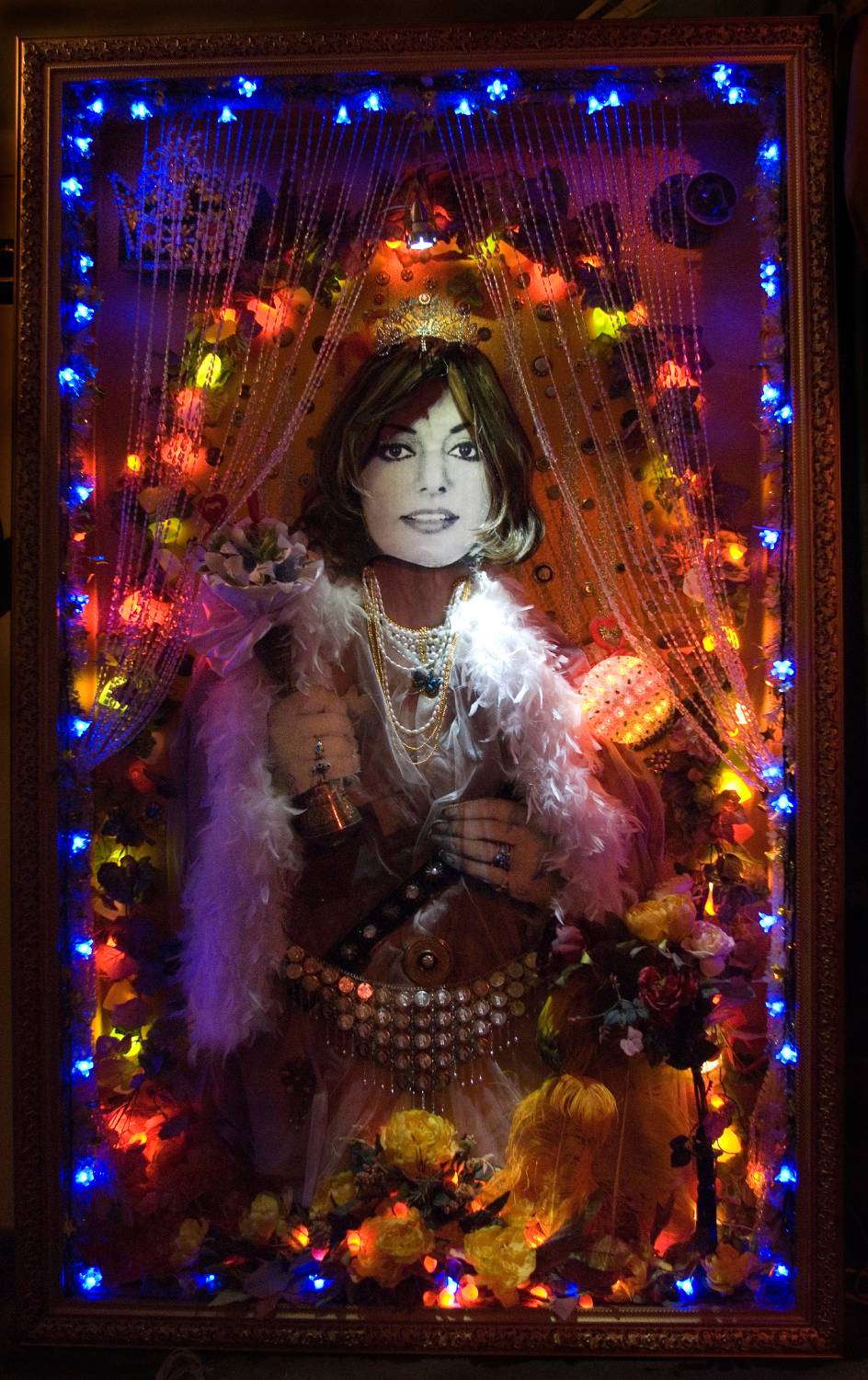

‘Ready to Order is a collection of three dimensional large-scale boxes; imagine busy window displays with ornate gilded Ready to Order frames. At the center of the boxes individuals both famous and unknown are immortalized with cardboard likenesses, positioned proudly and surrounded by their typical universe of objects – statuettes, tools of trade, family photographs, and glittery ornamentation in a play of flashing lights, garlands and plastic foliage.

The first word that comes to mind having discovered Khosrow’s seven boxes is most probably ‘kitsch‘,

It is a word often used but what is its full meaning? Turning to the dictionary, we find kitsch is ‘associated with sen-timentalism and bad taste’ and describes ‘works of art and other objects (such as furniture) that are meant to look costly but actually are in poor taste’. Whether it tries to appear sentimental, glamorous, theatrical, or creative, kitsch is a gesture emulating the superficial values of art.

Why then is it so popular? Thomas Kulka, in his book ‘Kitsch and Art’, explains it as follows: ‘They play on basic human impulses irrespective of religious beliefs, political convictions, race, or nationality. They exploit universal subjects such as birth, family, love, nostalgia, and so forth.’ And Hundertwasser said ‘The absence of kitsch makes life unbearable’. If kitsch has always been embraced in the popular realm, it is now unmistakably ensconced in the world of fine art. ‘Ready-to-Order’ can be interpreted as a gross parody of Iranian society and its aesthetics but also as an earnest effort to raise the craft of the unrefined artisan to the high street.

One can see ‘Ready-to-Order’ slogans all over the city of Tehran, on banners at the entrance of restaurants and hospitality halls, in daily newspapers and advertisements. The phrase is aimed at the typical Iranian habit to ‘commission and order’ on the occasion of all sorts of celebrations. Whether for a wedding, a birthday, a memorial for lost loved ones and religious martyrs or a funeral, what matters is that the host has ‘ordered’ a lavish banquet, a socially meaningful token of affluence. Initially inspired by the small boxes found in the holy birthplaces of Imams and the tombs of martyrs, Hassanzadeh likes to think of these custom boxes as shrines, his bespoke homage to unrecognized or otherwise uncelebrated subjects.

His choice of subjects for portraiture began with ordinary people like his mother, his friend, or himself and eventually evolved towards popular icons In one remarkable example, the famous diva Googoush appears from behind a beaded curtain, wearing her myriad glamorous accessories: a diamond tiara, a shiny costume with heavily jeweled belt, and a white boa. The background complements this opulence with fake flowers and blue lights. Another box is consecrated to the popular singer Javad, whose name has become an adjective which means ‘kitsch’ in Farsi. Wearing his best orange suit and tie, his edified figure adorned by lavish lily pads and sun flowers, he smiles amidst a background of mirror work and wall-paper depicting swans quietly swimming. The Pahlavan: beloved wrestler, paragon of physical and moral strength for the local population, carries serenely his championship medals and traditional costume while his instruments, photos and lucky charms crowd his box. Fired by passion, Hassanzadeh has explored every stable of the downtown bazaars to find the right objects to properly pay tribute to the diva, the pop singer or the pahlavan.

Yet, a democratic artist, he is known to be inspired by the ordinary people of his daily entourage, and even more by the dis-advantaged and abused, whom he is always ready to defend (see his Prostitute and Ashura series). That being said, Khosrow is willing to extend his services to anyone who would like to see themselves Ready to Order.