Pahlavan

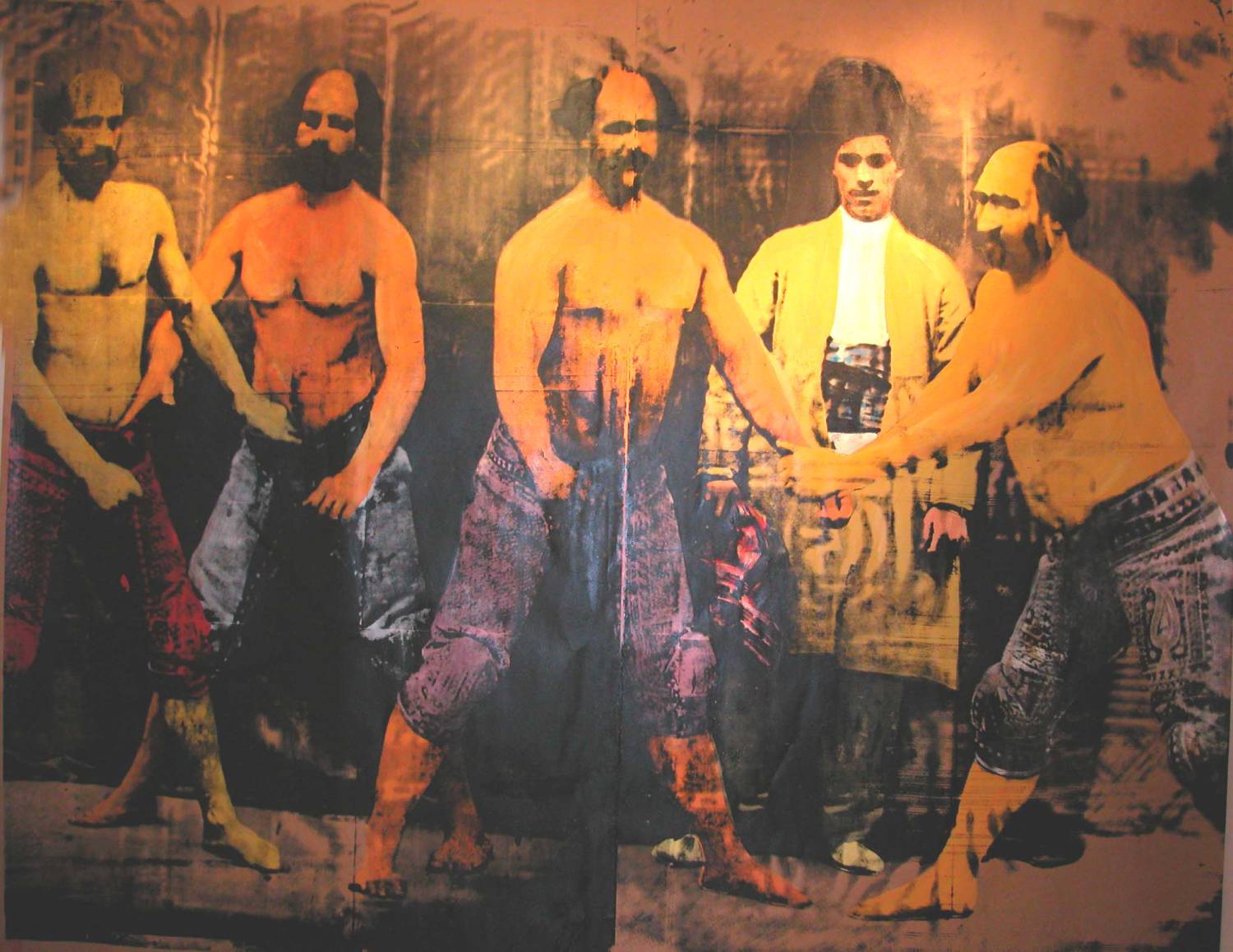

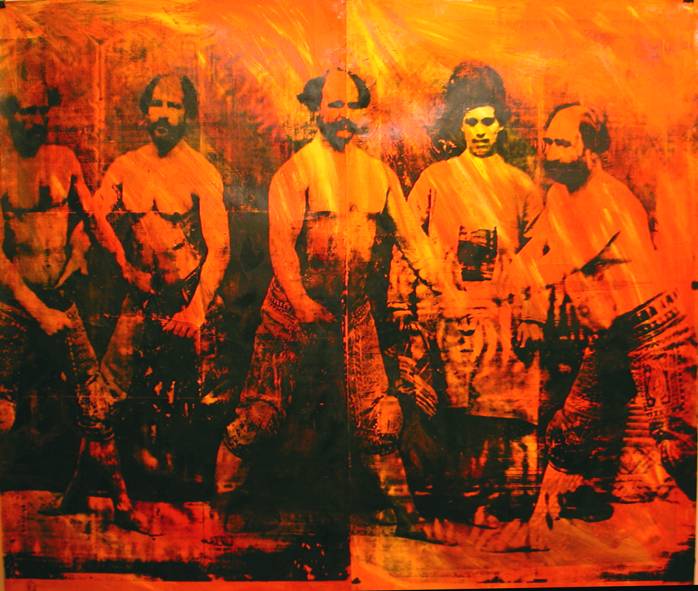

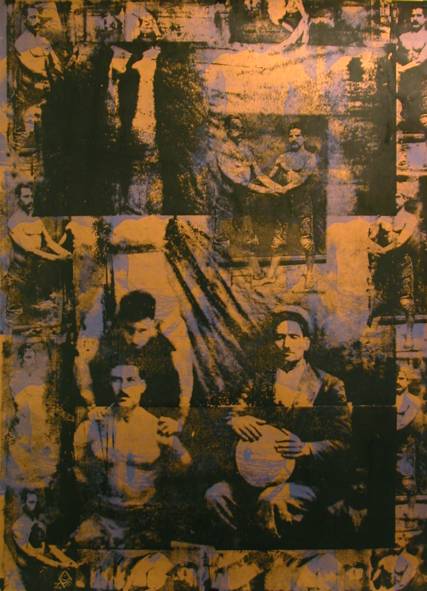

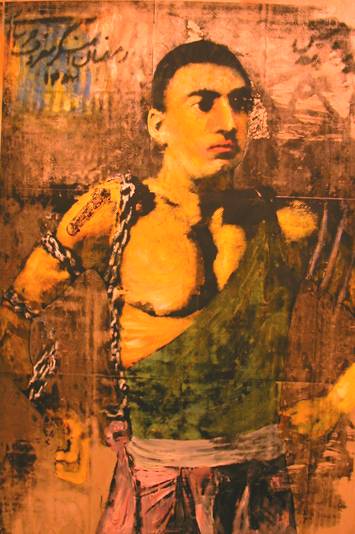

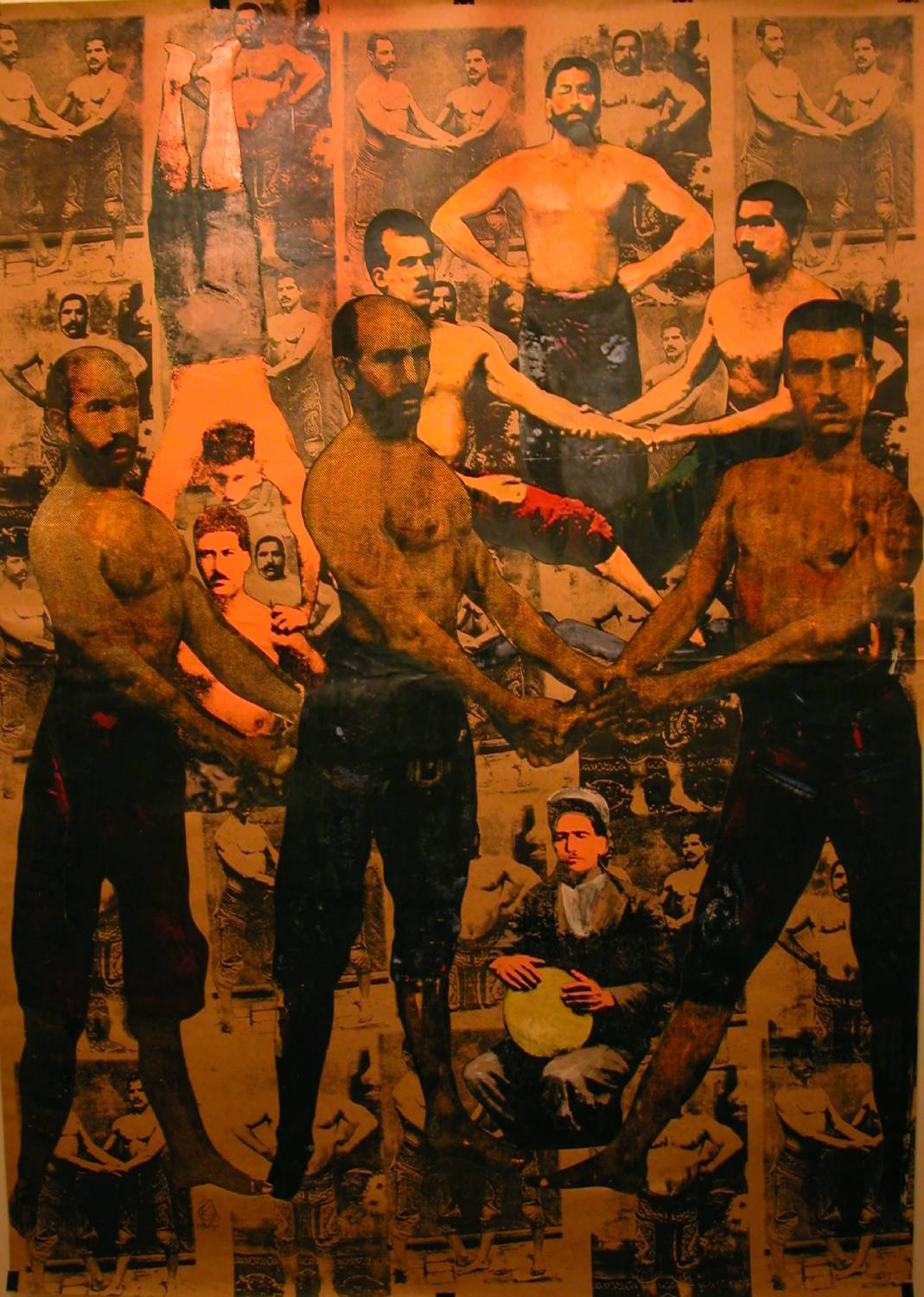

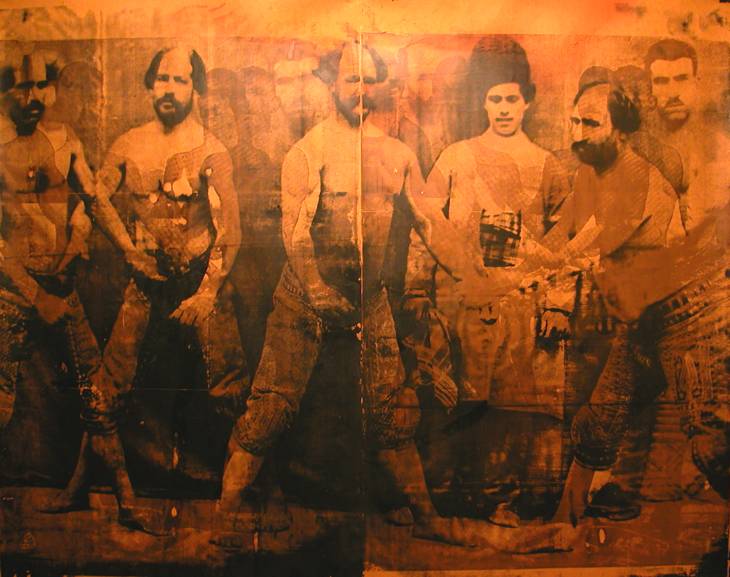

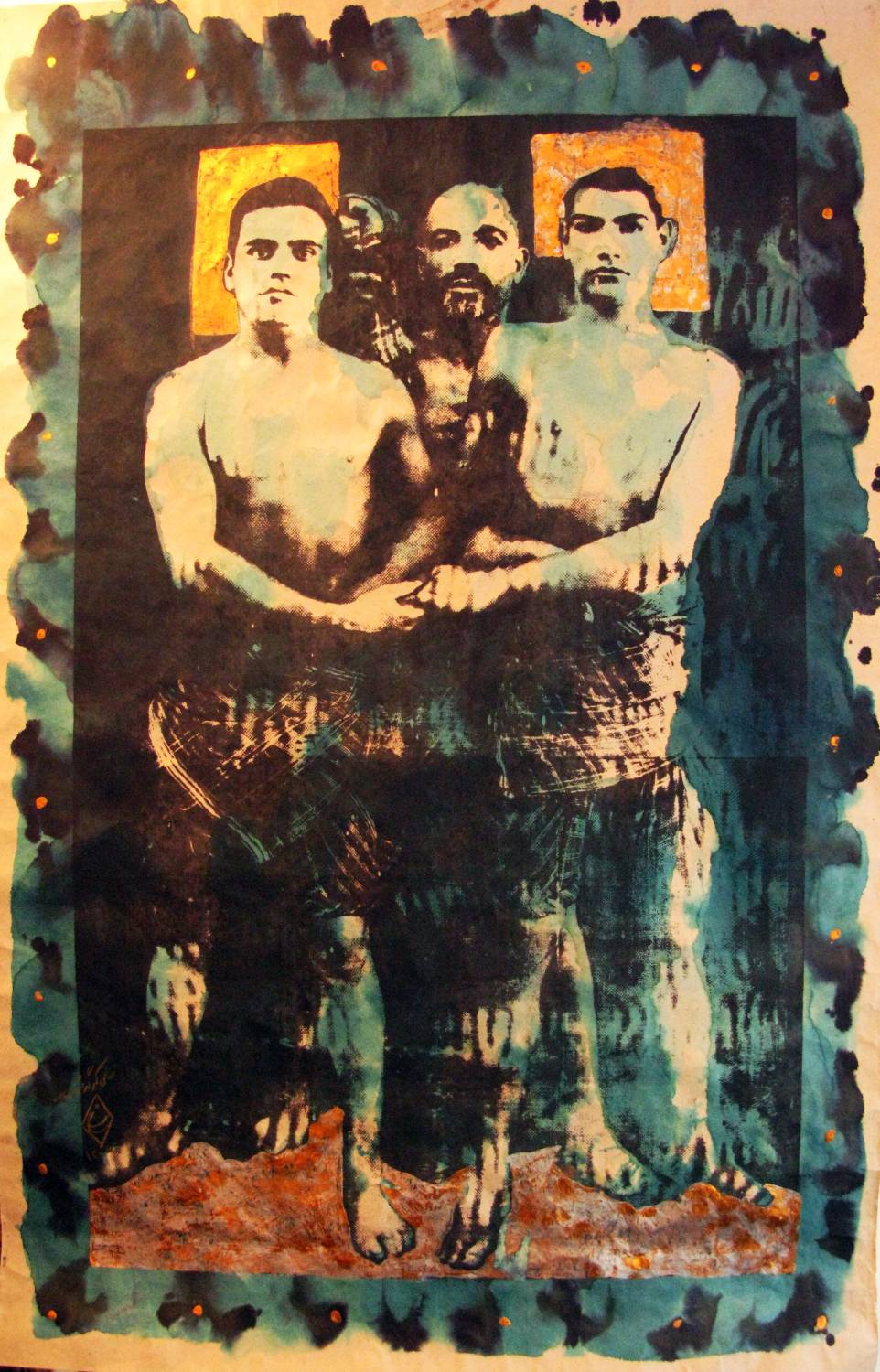

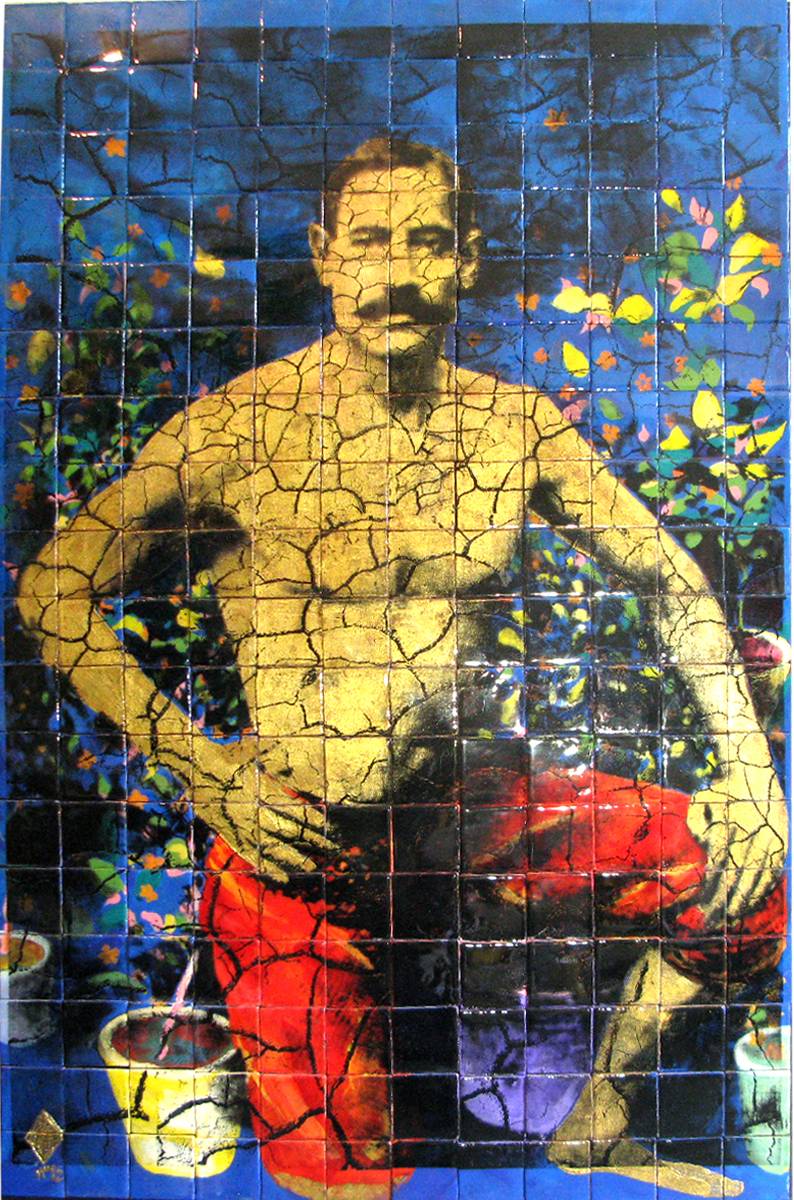

What links Khosrow Hassanzadeh to his Pahlavan series is more than a shared spirit of chivalry that these champion wrestlers, or pahlavans, represent. First comes the name: Khosrow as in Khosrow Parviz, the last great Sassanian King (reigned 590 – 628 AD). According to Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, or Book of Kings, a tenth century work of history in epic poetry, Khosrow was the lover of Shirin and trained in the arts of chivalry. The romantic story of Khosrow and Shirin is one of the most popular poems among the legendary, historical, and ethical poems that were recited for centuries in Iran. The Shahnama was not only illustrated in manuscripts but its illustrated epic poems also decorated the walls of most zurkhanahs of Iran. Known as ‘coffeehouse’ paintings today, one can find them in the traditional tea-houses and restaurants of Iran, along with early photographs of favourite champion wrestlers that are the inspiration for these monotypes.

A zurkhanah (house of strength) is a traditional gymnasium exclusive to Iran, dedicated to the development of men’s bodily strength, and ideally to spiritual guidance and the promotion of high ethical values of chivalry (javan-mardi). The exercises, combined with the rhythm of the drum and chanting of verses from the Shahnama, create a spirit of elation and chivalry. The pahlavans’ tradition somehow inhabits Khosrow Hassanzadeh who comes from the same social background, of downtown Tehran, where wrestling and weight lifting, now as then, remain the ultimate traditional sport.

When in 1980 the sixteen-year-old Hassanzadeh volunteered as a member of the basij, or self-appointed moral militia, to fight corruption and — later — to defend his country in the Iran-Iraq war, he must have been inspired by what the zurkhanah offered to pahlavans: an alternative to the religion of the mosque, and a centre for the ayyars (the local urban militia). Khosrow became well known for his courage during the years he fought on the Iran-Iraq front.

The Pahlavan series directly reflects the influence of the School of Saqqakhaneh, the Iranian ‘Spiritual Pop Art’ movement that was so important in the 1960s. In the years before the revolution, works by American Pop artists like Warhol, Rosenquist, Dine, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and Johns were acquired by Queen Farah Pahlavi for the collections of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Furthermore, Western Pop Art was one of the few art movements that escaped censorship in the rare books or magazines available in post-revolutionary Iran. The concept of Pop Art appeals to Hassanzadeh: ‘pop’ as in popular, urban, affordable, designed for a mass audience, expendable, low-cost, mass produced, and maybe glamorous. These iconographic images of past champions, reproduced serially and mechanically with different colour variations on paper, are witty and gimmicky remarks on the notions of chivalry and transience.